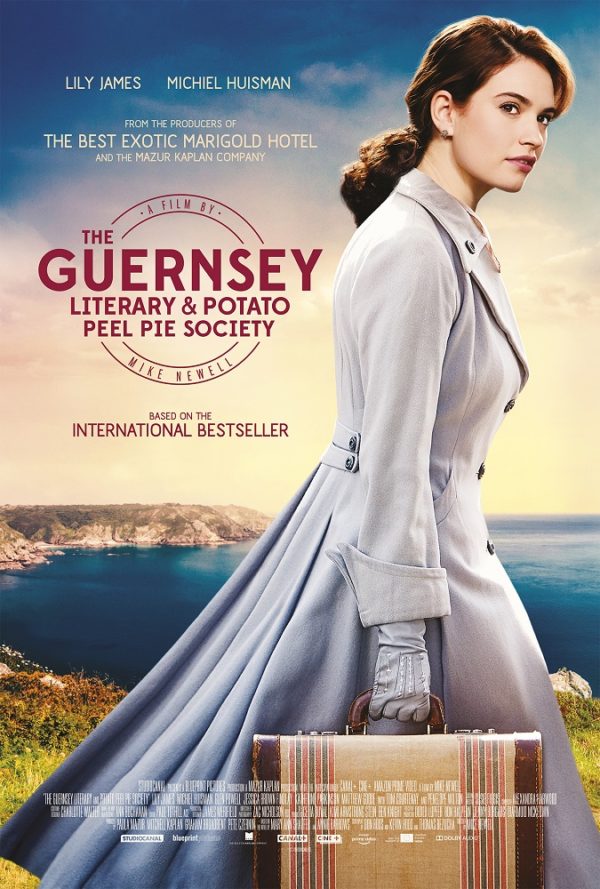

Director: Mike Newell 3 stars

The small audience at the Everyman preview burst into

applause at the end of the viewing and they showed their appreciation

throughout with much laughter at all the right places. Aaah, there’s nothing

like a cuddly rom-com to give you that feel-good experience. Reminder: Mike Newell

directed Four Weddings and a Funeral.

It is 1946 and Juliet (Lily James) is an author who is

contacted by a handsome Guernsey pig farmer Dawsey (Michiel Huisman) and

decides to visit the island to interview its book group for a newspaper article.

The group was a hastily invented ruse to fool the German occupiers but it has

kept going after the war. Now Juliet finds that there is a mystery which she

offers to solve with the help of her American GI boyfriend, Mark (Glen

Powell). So we get rom-com with the added

bonus of a nice little detective story.

It is 1946 and Juliet (Lily James) is an author who is

contacted by a handsome Guernsey pig farmer Dawsey (Michiel Huisman) and

decides to visit the island to interview its book group for a newspaper article.

The group was a hastily invented ruse to fool the German occupiers but it has

kept going after the war. Now Juliet finds that there is a mystery which she

offers to solve with the help of her American GI boyfriend, Mark (Glen

Powell). So we get rom-com with the added

bonus of a nice little detective story.

This is a film that will do well at the box office and we

will see it offered innumerable times on TV. It will soon be available on

Netflix. It is in the same genre as Their

Finest, Darkest Hour, Swallows and Amazons, The Best Marigold Hotel, Harry

Potter and Call the Midwife. It’s

about that imaginary time when things were apparently simpler and people had hearts

of gold beneath their gruff exteriors or else were properly evil. In this case

there are the horrid Germans and the one Good German, the stoical Islanders, a

token American who is nothing like as brilliantly fascinating as he thinks he

is, a cuddly old geezer (Tom Courtenay) and an isn’t-she-comical hippy-dippy character

who brews and drinks her own gin. Children are sweet and docile.

In the real life Channel Islands it is still difficult to

talk about the German occupation. There is shame, guilt and painful confusion,

not just about the occupation itself but about the way the aftermath was

handled because sometimes this was done without understanding, compassion or

mercy. In real life it is obvious now

that there were complex reasons why women had liaisons with German soldiers and

why both men and women were collaborators.

In real life, children whose mothers disappear are traumatized and act

out, they don’t smile politely, as in this film, for all the world as though

nothing terrible has happened.

In the universe portrayed by so many rom-coms there are no taxing

moral dilemmas or deep hurts and no shades of grey in human behaviour. It would

be a simpler world if you believed in the rules of rom-coms, for instance as

here, that the boyfriend with the smaller eyes is always the one you should avoid.

And that you are well rid of a man who makes off with the champagne after you

have rejected him – clearly he was always a rotter.

In the universe portrayed by so many rom-coms there are no taxing

moral dilemmas or deep hurts and no shades of grey in human behaviour. It would

be a simpler world if you believed in the rules of rom-coms, for instance as

here, that the boyfriend with the smaller eyes is always the one you should avoid.

And that you are well rid of a man who makes off with the champagne after you

have rejected him – clearly he was always a rotter.

As the film ploughed on, its superficiality began to

irritate me and I started to notice the details that felt wrong. How did Juliet

get all those hand knitted sweaters into her one suitcase? Where did her

typewriter come from? Why were British people

from 1946 using present day Americanisms where children are ‘raised’, phones are

‘picked up’ and people say ‘right now’ instead of ‘at the moment’? Where did

Juliet get her eyeliner and brown eyeshadow as I don’t think they had it in

1946? How come her American boyfriend was able to commission a US warplane to

make his romantic dash to Guernsey? Did he steal it?

Can you, all in one film, successfully combine historical narrative

with a gripping detective story with romantic drama? I guess you can’t and for me this film

doesn’t.

Never mind. The costumes are terrifically authentic (Charlotte Walter) and congratulations to the

finder of such splendid interiors along with the production designer (James

Merifield). They have all done a fine

job along with the distinguished cast, especially Penelope Wilton. However, if you go hoping to see a lot of picturesque

Guernsey landscape prepare to be disappointed as I have a suspicion that most

of it was shot elsewhere.

The actual highlight of the evening for me was in the ads, a

process that I normally avoid by arriving late. The new Lloyds Bank ad, The Running of the Horses

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=079qcLQkq1M

is a stunning piece of art, directed by Sam Pilling. That sixty seconds lives

on in my mind as conveying some kind of emotional truth, unlike the 124 minutes

of the feature film itself which I will most likely have forgotten by the end

of next week.