45 Years and All the Way set

Joe thinking about the indie advantage

There’s no such thing as a low budget novel. There are

genres that flourish at the margins, such as fanzine fiction, but most writers,

even those published by major imprints, are essentially indie operators. There

is certainly no obvious correlation between money and quality. Sentences can’t benefit

from high production values.

Films are different. To shoot a film some outlay is required

in addition to food and lodging for the auteur. There are kinds of quality that

cost money. Which is why I’ve always had mixed feelings about independent low

budget movies. On the one hand they’re less likely to be corrupted by the

corporate imperative to maximise profits. On the other, they’re more likely to

be spoilt for a ha’p’orth of tar.

Flying to LA for Thanksgiving with my California in-laws I

had plenty of time to think about this while I caught up on new releases.

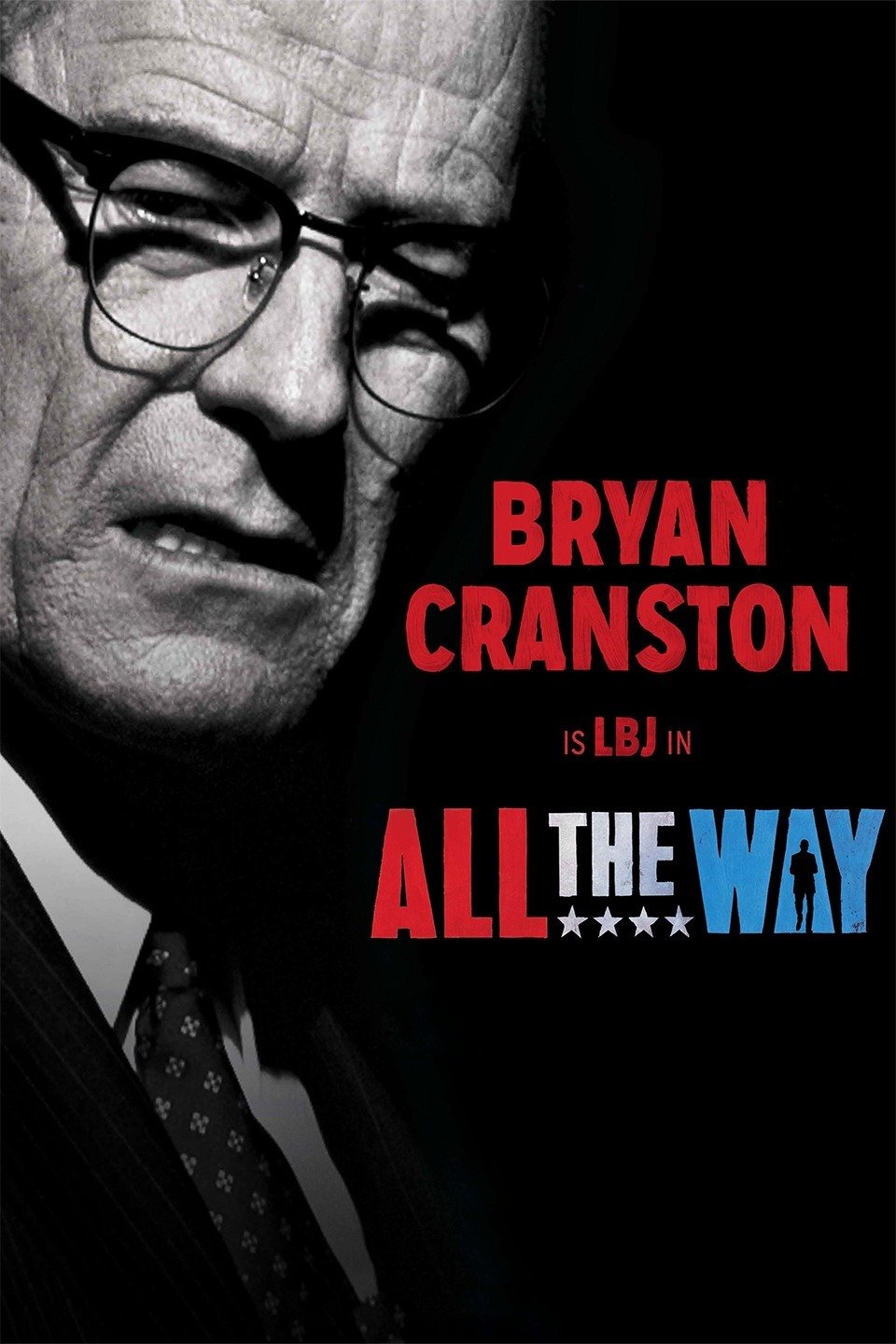

All the Way covers

Lyndon Johnson’s first year in office, from his sudden elevation to the

Presidency after JFK’s assassination to his victory in the 1964 Election. Huge

historic changes are in progress as Johnson manoeuvres to get Kennedy’s Civil

Rights bill through Congress, even at the cost of alienating Southern

Democrats. Bryan Cranston, who came to fame as the drug-dealing chemistry

teacher in Breaking Bad, gives a superb performance as LBJ, confronting us with

a paradoxical figure – often crude, sometimes bullying, but capable of great

charm and driven by a genuine urge to reduce poverty and oppression in America.

All the Way covers

Lyndon Johnson’s first year in office, from his sudden elevation to the

Presidency after JFK’s assassination to his victory in the 1964 Election. Huge

historic changes are in progress as Johnson manoeuvres to get Kennedy’s Civil

Rights bill through Congress, even at the cost of alienating Southern

Democrats. Bryan Cranston, who came to fame as the drug-dealing chemistry

teacher in Breaking Bad, gives a superb performance as LBJ, confronting us with

a paradoxical figure – often crude, sometimes bullying, but capable of great

charm and driven by a genuine urge to reduce poverty and oppression in America.

I watched with enjoyment and admiration, but remained

emotionally unengaged. HBO and producer Stephen Spielberg haven’t stinted on

sets and locations. The research was thorough. Adapted from a play, the script is

sound, if a bit too earnestly instructional at times. There’s fun to be had,

particularly in the relationship between LBJ and his running mate, Hubert

Humphrey, played by a heavily disguised Bradley Whitfield. The hapless Humph

has a moment of panic when Johnson pretends to lose control of his car and

drives it into a lake. It’s only then that we discover it’s amphibious. That’s

the kind of thing you can do with a decent budget.

The letter, written in German, sends Geoff and Kate into the

garage in search of his old German dictionary. The film is punctuated by these

encounters with old possessions, first in the garage, later in the attic, first

together, then separately as the strains on their relationship begin to show.

Katya was dead before Kate met Geoff, but a dead lover who has never suffered

the ravages of aging is hard to compete with.

At the heart of the film is a sequence in which Kate, having

found Geoff’s slides of his 60s travels and set up an old projector in the

attic, clicks through images of Katya, first small in the landscape, then in

close-up. We see the two women side by side, Kate staring intently at the

screen, Katya looking at the unseen photographer. Visually beautiful, this

series of images delivers a narrative jolt sharper than anything in All the Way, though in Hollywood terms

it cost nothing.

Accepting another gin and tonic off the steward’s trolley, I

concluded that, in this pairing at least, the indie film had all the

advantages.