Joe questions the premise of Eye in the Sky

If you like the kind of thriller where stuff gets blown up

and no one has time to count the bodies, you’ll be disappointed with

Eye in the Sky. Writer Guy Hibbert and director Gavin Hood make us wait

for most of the film while an expanding circle of military and political

figures agonise over whether to authorise a single precision drone strike and how

to minimise the human cost. The result is more like a seminar in moral

philosophy than an updated

Airforce One.

The set-up is designed to present an excruciatingly balanced

ethical conundrum. In response to information that senior figures in the East

African terrorist group Al-Shabaab will be gathering in Nairobi, Colonel

Katherine Powell (Helen Mirren) is directing an operation by Kenyan ground

troops to pick them up. When the terrorist meeting is moved to a house inside a

camp controlled by extremists, a no-go area for the military, Powell sees no

alternative to a drone strike.

Overseeing this operation from Whitehall is Powell’s

commanding officer, Lieutenant General Frank Benson (Alan Rickman), the British

Attorney General, and a couple of government ministers. From a US air force

base outside Las Vegas, two young American drone pilots operate the “eye in the

sky” of the film’s title and wait for instructions.

Meanwhile the stakes are rising on both sides of the

question. It turns out Powell has in her sights not only three “high-value

targets”, identified as numbers 2, 3 and 5 on the US President’s East Africa

kill list, but also two suicide bombers who are even now suiting up to go out

and create carnage in some public place at an estimated cost of 80 lives. Who

could resist zapping the lot of them in one go? Random deaths will be limited

to a small area around the house. But a child, who has previously been observed

playing safely in her own back yard, sets up a stall in the street selling

bread. For all those watching the live footage this

girl’s fate becomes the central question. Can they strike without killing or

injuring her? Should they strike anyway?

At the level of human drama, the film is absorbing. But I

found myself increasingly distracted by a feeling that the debate was skewed. In

their charismatic performances, Mirren and Rickman seem to represent the

military at its most admirable, doing what has to be done to keep us safe. The

US politicians, who appear only briefly, are cartoonishly gung-ho. It’s left to

the British politicians, agonising over biscuits and coffee in their plush

Whitehall office, to consider the case against action. But they’re a weaselly

bunch, worrying how they’ll explain themselves on the Today Programme if it all

goes wrong and the footage is leaked to you tube. Rickman, required to seek

ever higher clearance, gives a characteristic performance of deadpan disdain

(sadly his last). This raised uneasy chuckles from the elderly matinee audience

in the Clapham Picturehouse. I imagine less thoughtful audiences might howl

with derisive laughter at the cowardly buck-passing. But this isn’t an episode

of

The Thick of it: these politicians

are clearly sweating their way through a dilemma that has a moral dimension for

them as well as a political one.

It occurred to me only afterwards that the way the film maintains the illusion of balance is by piling up the rational case in

favour of the drone strike and the emotional case against.

The argument for saving the child, played enchantingly by

Aisha Takow, is given emotional weight for the audience who get to know her at

ground level. We learn that her father does nothing more dangerous for a living

than mending bicycles, that her mother bakes the bread that she sells in the

market, and that they are explicitly not “fanatics”, the term her father uses

for their neighbours. In the privacy of the home, she studies maths and in the

yard she plays charmingly with a hula hoop, though her hula-hooping, like her

schoolbooks, must be hidden from visitors. All of which makes her, and her

parents, effortlessly appealing to a Western audience, while adding nothing to

the moral case for protecting her.

Rickman’s character, resistant to such sentimental concerns,

takes the pragmatic view: “Save her and risk killing 80 others.” The nearest

thing we get to an answer comes from one of the British politicians: “If

Al-Shabaab kills 80 people, we win the propaganda war. If we kill one child,

they do.” This is a powerful argument fatally weakened by its acceptance

of the General’s assumption that drone strikes save lies – calculably and

immediately. No one in the film questions this, nor the long-term strategy of

assassinating replaceable individuals while alienating civilian populations who

must live under the constant threat of random aerial attack.

It’s a junior minister, played engagingly by Monica Dolan,

who offers the most consistent objection on moral grounds, but the script gives

her nothing to say in response to Rickman’s sonorous last words: “Never tell a

soldier that he does not know the cost of war”. This final stand-off between

the agitated, damp-eyed civilian woman and the sorrowfully determined General symbolises

the heart-versus-head premise on which the film is constructed.

Persuasively written, superbly acted, convincing in its procedural

details, Eye in the Sky left me

feeling emotional manipulated and intellectually bamboozled. The argument for

risking the child’s life is unrealistically contrived. The give-away is the

addition of the suicide bombers and the confident estimate of 80 imminent

deaths. In the war we are conducting with daily drone strikes in many

countries, how often, I wonder, does a drone pilot have in his sights a suicide

bomber on the point of detonating his vest? We’ve become used to the

justification for torture that was regularly represented in Fox’s long-running

series, 24. Wouldn’t you torture

someone if he could direct you to a bomb in time for you to defuse it? This

film seems to offer an equivalent defence of drone strikes.

In the desperate circumstance presented in this story, a little corruption seems justified. When Mirren’s

character, having struggled conscientiously throughout to do what’s best, makes

the first move towards a cover-up, I felt invited to consider the lonely burden

of responsibility carried by those charged with protecting us, because, as

another fictional colonel once famously remarked, we can’t handle the truth. Sadly

there’s no one in this film with the eloquence or the stature to challenge that

dangerous falsehood.

And after the General has had his say and the verbal debate

is over, it’s only the closing wordless sequences, in a hospital

in Nairobi and on an Air Force base in Nevada, that suggest the devastating

cost of such actions – to the innocent victims, of course, and to the

anti-terrorist cause, but also, less obviously, to those who fire the missiles

in our name from a distance that keeps them physically safe but cannot protect

them from the emotional and moral cost of what they are required to do.

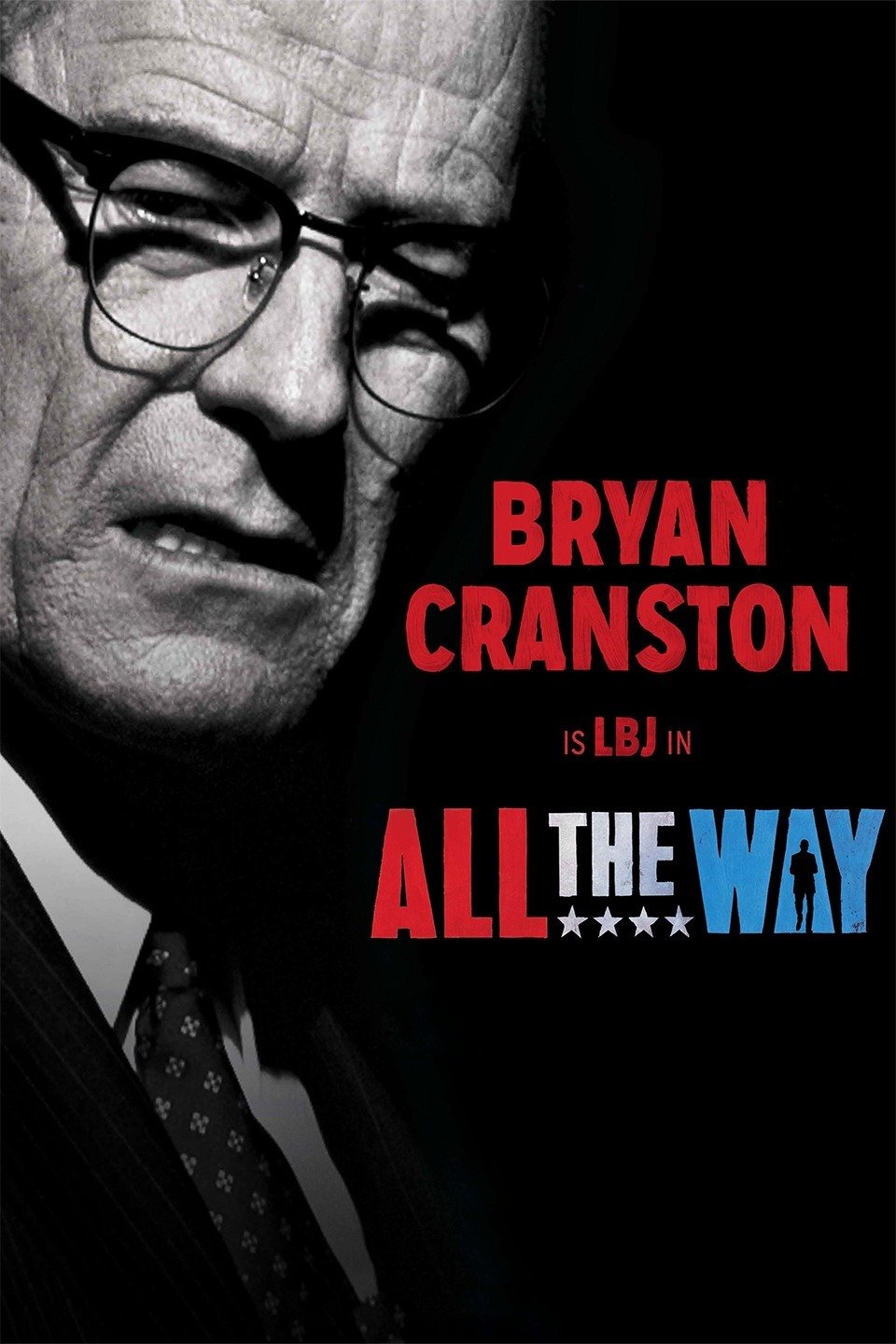

All the Way covers

Lyndon Johnson’s first year in office, from his sudden elevation to the

Presidency after JFK’s assassination to his victory in the 1964 Election. Huge

historic changes are in progress as Johnson manoeuvres to get Kennedy’s Civil

Rights bill through Congress, even at the cost of alienating Southern

Democrats. Bryan Cranston, who came to fame as the drug-dealing chemistry

teacher in Breaking Bad, gives a superb performance as LBJ, confronting us with

a paradoxical figure – often crude, sometimes bullying, but capable of great

charm and driven by a genuine urge to reduce poverty and oppression in America.

All the Way covers

Lyndon Johnson’s first year in office, from his sudden elevation to the

Presidency after JFK’s assassination to his victory in the 1964 Election. Huge

historic changes are in progress as Johnson manoeuvres to get Kennedy’s Civil

Rights bill through Congress, even at the cost of alienating Southern

Democrats. Bryan Cranston, who came to fame as the drug-dealing chemistry

teacher in Breaking Bad, gives a superb performance as LBJ, confronting us with

a paradoxical figure – often crude, sometimes bullying, but capable of great

charm and driven by a genuine urge to reduce poverty and oppression in America.

.jpg/220px-Florence_Foster_Jenkins_(film).jpg) Florence Foster Jenkins is the story of a wealthy woman who can’t sing yet who hires the Carnegie Hall in 1944 to give a recital. Her records, recklessly made because she believed so firmly in her own talent, became best sellers, but for all the wrong reasons. Her personal and business partner, a former actor, St. Clair Bayfield, had been able to keep the proper critics away up until that point through a mixture of persuasion, bribery and threat, but this became impossible with a public concert in such an enormous place. Professional critics demolished her performance and she died shortly afterwards.

Florence Foster Jenkins is the story of a wealthy woman who can’t sing yet who hires the Carnegie Hall in 1944 to give a recital. Her records, recklessly made because she believed so firmly in her own talent, became best sellers, but for all the wrong reasons. Her personal and business partner, a former actor, St. Clair Bayfield, had been able to keep the proper critics away up until that point through a mixture of persuasion, bribery and threat, but this became impossible with a public concert in such an enormous place. Professional critics demolished her performance and she died shortly afterwards.